A recent conversation at home went like this:

Me: "Hey, honey, did you say you needed new hiking shoes?"

Wife: "Eventually. Mine are starting to wear. Why?"

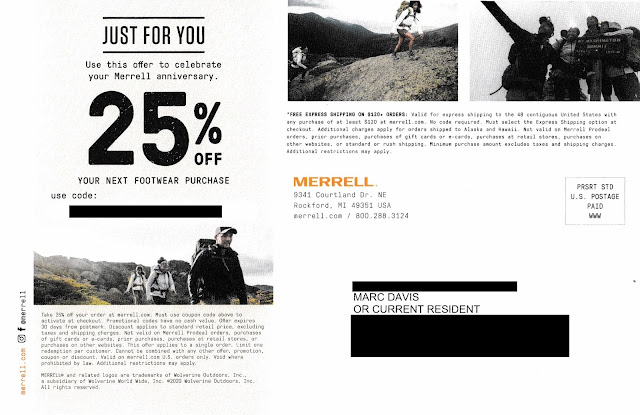

Me: "We got an offer in the mail from Merrell for 25% off footwear."

Wife: "Well, I do like Merrell, but I don't plan to use hiking shoes in the next few weeks. Maybe I should get replacements now with the discount. When does the coupon expire?"

Me: "It doesn't say."

Wife: "Really?"

Me: "I'll look closer." (Puts on reading glasses.) "It says it expires '30 days from postmark.'"

Wife: "When is that?"

Me: "I don't know. It's not postmarked."

Wife: "Well, whatever, I don't need new hiking shoes right away and I'm pretty busy right now."

This conversation outlines why the postcard merits a Fail for Creative.

On September 13, 2019, I purchased a pair of Merrell Moab 2 hiking shoes. They are perfect for that outdoor hike around the lake, through a park or in the snow. The postcard arrived October 2, 2020, just a little over a year after I started wearing my previous purchase. So, the timing and messaging around my "Merrell anniversary" are spot on. Kudos to Merrell for Timing.

The postcard included a personalized coupon code for 25% savings; however, there is no mention in the headline regarding when the coupon code expires. I found some information in the disclosure.*

|

| Postcard disclosure text |

As I wrote in prior blog posts such as this one and this one, a Call to Action should include a clearly communicated offer expiration date. This is important: The right response window encourages immediacy of customer action; one that's faulty or unclearly defined, however, only encourages inertia.

With the Merrell postcard, the coupon code's expiration date is not only buried in the disclosure, it also references expiring "30 days from postmark"; however, there is no postmark. Postcards mailed Standard Rate are not postmarked by the USPS. So, how do customers know when the coupon code expires? They don't.

There are several ways to care for expiration date communication without jeopardizing the integrity of the message, diluting Merrell's branding or adding production costs. Here is one: Include an offer expiration date in the address section of the postcard.

|

| Mock-up. I added the expiration date in the address panel |

In the above mock-up, the coupon code expiration date is clearly communicated. The date is specific and reasonably prominent. The messaging complements the headline and supports immediate action. It can be inkjet- or laser-personalized using the same variable data method as the producing the coupon code and customer name and address. Depending on the postcard's production method, it could appear in spot color without incremental print expenses.

If Merrell adapts this approach, the only incremental edit would be to rephrase the disclosure to reference the expiration date in the address panel.

Lessons:

- Your call to action should include a clearly communicated, definitive offer expiration date.

- Postcards mailed Standard Rate are not postmarked.

.png)

.png)